Lasercut

After weeks of discussion and exploration Emma and I came to the decision to focus on offensive gestures. And to use this as a starting point to research and develop our work, with no jumping to designing the final outcome.

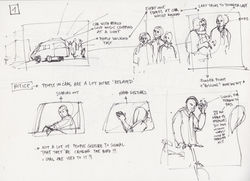

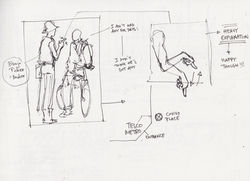

It was my idea that we should go out for a full day and observed people. We had set each other places to sit and draw, and at the end of the day came together to look through the drawings. Emma went to the market and Haymarket. And I was overlooking the high street and at the forum. From this day, we found out that I was heavily focussed on hand movements and how odd they seem without context. Is it possible to represent a hand movement through simple, quick drawings? Whereas Emma’s drawings are much more to do with the surroundings, including the buildings and the whole character. Is all of the environment important, or are there significant elements?

We instantly saw the juxtaposition in our working methods. I have fluid movements, it was a natural way for me to hastily represent what I was seeing. Every sketch I made was done quickly, as the fleeting nature of the gesture. Where Emma’s had a sense of scene setting, like she is telling you that all the rest is also important to fully understand the situation and why this gesture is being used.

Amanda's images above

Emma's to the right

View Finders

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We chose shapes from each drawing; half focussed on gestural movement, and half on situational context. And tested these out using cardboard.

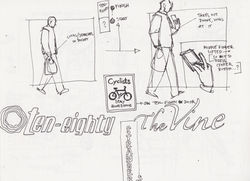

The next few days we spent developing observational drawings around Norwich. From our understandings of each other’s drawings we built upon our own initial drawing techniques. I spent time looking and appreciating the place, whilst questioning the important elements to represent in the drawing. There were aspects of the place that would alter how the people interacted with one another, and these are the elements I wish to represent through my drawings. There are components of situational context that will affect the people within it, for example pathways and shop fronts. And these parts are all designed to be used or seen in a certain way. Emma had been naturally including the situational context, but was beginning to explore the use of hierarchy in order to emphasise the gestures that we are researching.

We concluded we wanted to draw attention to the gesture, as well as the significance of elements of surrounding. It was from this idea of picking and prioritising elements of the observation that we thought upon viewfinders. A lens in which you are forced to see a particular part of the bigger picture. From our drawings we are going to make set of our own shaped viewfinders.

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|

Considering the effectiveness of our cardboard cutouts, we deliberated on how we could develop them further. The idea was to make them into objects with a more stable or transferable format. Our first thought was, instead of doing them by hand, using a laser-cutter in the media studio. Ultimately this would allow us to produce refined outcomes with stronger, more enduring materials.

The initial cardboard cutouts were all uneven in size: this made them difficult to handle, even more so to layer them on one another. We knew that our laser-cut prototypes would have to be same shape and have the same dimensions in order to make them easier to manipulate. After pondering a few possibilities, we chose to make them square: as a recognizable geometric structure with equal sides and angles, it naturally delineates stability and balance. The square brings the viewer’s attention to the contours of the empty space at the center of each object, accentuating the forms cut out of the surface. We are creating a physical view finding frame.

“Using the square format encourages the eye to move around the frame in a circle. This is different to the rectangular frame, where the eye is encouraged to move from side to side (...). The square is such a powerful shape that it emphasises other shapes within it.”

Andrew S. Gibson (photographer), 6 Lessons the Square Format can teach you about Composition (2013)

An essential function for these objects was that they could be stacked one on top of the other, in reference to the idea of layers composing a sequence to a story. Bearing this in mind, we thought about how we could make this an interactive piece for audience members. Amanda found a solution quickly, in that each frame would have a 12mm in diameter hole cut out at the same exact position. This would allow a bolt to be passed through, linking each individual object together at their upper-left corner. Compositions would then be secured with a nut, and every layer could then be rotated or fanned out. Simple but incredibly effective, this became a defining attribute of our laser-cut works: audience members can select any frame and attach them together, thereby creating their own publication. I was certain that did not want to create a pre existing hierarchy to the elements we have chosen to represent, it is the participant's decision what they will include, therefore all ‘pages’ will be equally sized.

When selecting a material with which to make them, we established that it had to be:

-

strong enough so that the objects would suffer little damage if dropped or handled a lot

-

light enough for the objects to be easily held and manipulated

-

agreeable to touch and look at.

We chose to make our first prototypes using sheets of MDF with 2mm thickness, as it fit all the necessary criteria and each piece is divided into eight 15cmx15cm squares.

As a first attempt, we produced a total of sixteen prototype MDF laser-cuts based on shapes we had edited out of our observational drawings. Half of them from Amanda’s drawings on gestures, and the other half on my situational drawings including environments and objects.

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |

Original Environments

Almost immediately after cutting the MDF pages Emma and I both decided we had to take the shapes back to where we had drawn them. We desperately wanted to know how the images would sit among the original environment we had found them in. The cutouts are representative of quick passing moments, in a way that allows them to survive far longer as a part of the environment.

It was also a good way of testing the concept of the cutout as a viewfinder, a window into the environment. I guess the question here is how much can the gestural shape influence our interpretation of the surroundings?

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

Original Drawings

The idea to look at the MDF cutouts over the original drawings was born from a couple of other people who were looking at our work and questioned where the shapes came from. We had told them about the process of the places, the drawings, then the simplification for laser cutting; there was a lot of interest into the origins of the many abstract shapes.

One thing I was aware of was the selection process of the forms, we each studied our own drawings and chose elements that seemed the most important to us. For the observational drawings we had learn to prioritise the content, and we were doing this again to create very minimal abstract shapes to lasercut; we were really narrowing down the complicated concept of expression as gesture.

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

Emma's images

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

Amanda's images

Obscurity

Emma and I always have in mind the ability to make our ideas interactive, and this means never fully knowing how the public will react to the work. How do you make the work engaging and understandable?

With the unpredictability in mind I created a series of photographs looking at the many ways the MDF pages could be held or explored. I made a rule for myself that each cutout shape had to be slightly obscured in some way by the hand holding it. The process allowed for an exploration of the oddness in the design of a hand, and also how the cutouts echo the shape of a hand. We have created a lens that can be understood in many varying ways.

Quotes as Layers

I had never thought about the importance of the wording that often goes along with an offensive gesture, and it wasn’t until Emma mentioned it we began looking over her drawings again. She had often noted down words or quotes from the scenario and these really helped imply the mood to the drawing.

From the previous lasercut trials, we had a set of pages that were unsuccessful and were engraved with the detail rather than cut. I added the quotes to the failed pages, to see if the layering effect would still be legible, or if it may become confusing. As it turns out the layers allowed much more detail to be seen, however having it flatten to one layer was restraining. Perhaps we could have the quotes on another page that could be moved and layered with multiple pages? The quotes help thoroughly to suggest a negative emotion behind the offensive gesture, and is an idea we will definitely be building upon.

Conversation

Offensive gestures are a highly recognisable part of human communication: across all ethnicities and age groups, everyone can somehow relate to being offended or offensive through gesticulations. Knowing that these gestures originate and evolve through the intricate structures of social interaction, we immediately sought out an opportunity to talk to people about their personal experiences.

Our aim was to gain a deeper, more involved understanding of the subject we were investigating, as well as explore how certain gestures could be considered offensive in different contexts. Although we didn’t want to limit our investigation to a specific community, we had to take into consideration that this was quite a problematic topic to bring up in a public environment, and that our intentions could easily be misinterpreted. Bearing that in mind, we decided that we would conduct all interviews in a safe and comfortable location. Given that sharing opinions or personal experiences related to offensive gestures could prove to be challenging, we also thought it best to start by conversing with peers: it’s always easier to open up to someone you know, rather than someone you’ve only just met.

After careful consideration, we decided to set up an interview space within the third-year illustration studio, inviting fellow students from different courses at the NUA to take part in a friendly chat about offensive gestures with a cup of tea and biscuits.

In order to set the tone for our subject and motivate exchange between us and the participants, we implemented a few tasks relating to our work and devised a chronological order in which they would take place: [will draw up structure of space in which interview-workshop took place here]

Step 1 - A brief photoshoot in which each participant is asked to think about the most offensive gesture they know, and then act it out in front of the camera.

Step 2 - Participants are invited to sit down with a hot drink and share thoughts, stories or points of view about offensive gestures. They are also encouraged to handle and create a composition with the MDF laser-cut frames, nuts and bolts displayed on the table during the conversation.

Step 3 - Second photoshoot in which each participant is asked to pose with their laser-cut composition; “mugshot” session.

We arranged the space accordingly with clearly delimited sections for the interviews and photoshoots to take place, making it easy for people to navigate in and around the area.

The interview-workshop took place on the 6th of April 2017: taking into consideration that it was a very busy time for fellow students, potential participants could approach us whenever they had time to spare during the course of that afternoon, in a rather laid-back ambience. As well as photography, our chosen methods for data-collecting included sound and video recording; although the equipment was discreetly placed within the space, everyone was asked if their participation could be documented.

Several people partook in our interview-workshop during those four hours sharing their personal stories and point of view about offensive gestures. Each participant was willing to follow our established process, and the discussions we had turned out to be quite varied in nature, which became absolutely invaluable to the development of our work.

As I expected, unthought-of or underdeveloped aspects relating to our chosen subject were brought up as we conversed in small group of three or four. These included; the introduction of new contexts such as gestures while driving, offensive behaviour in bars or nightclubs and work environments, the relevance of gender in certain situations like heckling and sexually explicit gestures, and how offensive gestures evolve and change over time with generational differences, reinventing gestures, fads and trends.

Responses to the laser-cut frame exercise were very positive. As well as having something to touch and handle when talking, participants recognised certain gestures and locations depicted through the shapes, which in turn, encouraged fluid transitions from one testimony to the next.

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

Observations and development

“speech and gesture

co-expressively embody a single underlying meaning, a meaning that is the point of highest communicative dynamism at the moment

of speaking”

- David McNeill

By sharing our own experiences and relevant research with participants, we were able to engage in more in-depth discussions about what makes a gesture offensive in relation to environment, circumstance and individual perspective. When listening back to recorded conversations, we observed several interesting points we wanted to elaborate on further:

-

Most of the people we interviewed acknowledged that well-known emblematic gestures, such as the middle-finger and the V-sign, would not really cause them any offense. Given that these hand-symbols are so easily recognisable and can be seen anywhere, we learn how to manage them in various social contexts easily. We do them to friends quite freely for a laugh, but generally know to avoid acting them out in front of family members or children.

-

This attests to how human interaction and daily communication continues to evolve through time, but also begs the question: are certain traditional emblems still offensive? Or does it still depend entirely on their context? If they are no longer used to offend, than what is their purpose?

-

A few participants mentioned situations in which they weren’t sure whether or not they should be offended by an individual’s actions towards them. Depending on the nature and intentions of a person it can be difficult to determine exactly what they mean to express through gestures and language. What is deemed acceptable behaviour can vary so greatly from one individual to the next, we’re often at odds with what we feel and how to react for fear of misinterpreting what someone wants to imply. So where do we draw the line between respectful and offensive behaviour? Do we determine this ourselves instinctively over time? How important is our cultural background in relation to what we consider offensive?

-

Interestingly, some participants spoke about using offensive emblems in such a way that they would remain hidden from the people they were directed at. Examples of this include flipping someone off behind their back, or discreetly giving someone a V-sign by keeping your hand just under a car-door window. Arguably, this desire to express negative thoughts without actually offending anyone can be linked to Aristotle’s difference between anger and aggression; what starts off as a strong feeling can be exhibited through changes in behaviour. However, the sentiment may not be directly communicated to the individuals involved. (ref to philosophic/psychological theories) This could also be perceived as a demonstration of social self-preservation. Negative reactions are expressed cautiously, thereby avoiding any confrontation which could lead to a fight. That being said, do these gestures still qualify as offensive? Or do they have to be witnessed and actually cause offense for them to be regarded as such?

-

A crucial aspect of how we use hand gestures is their intrinsic relation with spoken language. As defined by Dr. Anthony Kong, the word gesture “refers to the arm and hand movements that synchronize with speech” (Hargie, 2017). Whether emblematic, illustrative or regulative, gestures can have a direct verbal translation always helping to convey what a person is trying to communicate. Whilst talking with participants the importance of language in relation to our subject matter was reaffirmed, to a point where one can’t really be detached from the other. It was mentioned many times that part of the joy of expressing negative thoughts through gestures was that you could combine them with appropriate words, which can actually maximise their offensive potential. Another interesting observation was the familiarity of verbal responses when feeling offended: “Did that just happen?” or “Excuse me?” are phrases we frequently uttered when someone is unexpectedly rude or aggressive towards us. This brought about questions relating cultural identity: how similar or dissimilar are we in our offensive and defensive reactions?

New places

Throughout the discussions there were three main places that seemed to keep coming up; Prince of Wales road, Exchange street and St Georges street. All of these places had stories attached to them through offensive gesture and language, therefore we decided to do further observational drawings within these areas. We split the places, Emma took exchange street and I went to St Georges street. Prince of Wales road seemed to have the worst and most stories attached, so we decided to both visit here, although we made the decision to go separately in the hope we would see varying content.

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

Amanda's drawings from

St Georges Street

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

Both our drawings from

Prince of Wales

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

Emma's drawings from

Exchange Street

Architecture

All of ours drawings now hold three differing elements. Whilst we still focused on gesture, we also included parts of the place and overheard quotes. We established throughout the conversations that language had an effect on the gesture; a concept we explore further within the cement mould based project. However through our observational drawings here we are able to recognise changes in behaviour, including gesticulations, due to the physical surroundings.

It is architecturally recognised that a building’s shape and material can alter how we feel about the environment. Therefore every designed building surrounding us must have an influence on our moods and therefore expressions. And if a physical environment can have an affect on us, then surely it can also tell us some detail to the intention behind the gesture. It is something we will continue to develop and consider.

“The environment can facilitate or discourage interactions among people…(and) can influence peoples’ behaviour and motivation to act.”

- Kreitzer, M J (2016)

Language

At this stage of development, we could clearly perceive how important the use of language was in relation to our subject matter. The interviews conducted during our workshop helped us reaffirm what we knew about role of gestures in body language: with the exception of emblems, which have a “direct verbal translation” (Hargie, 2017), they are essentially hand-movements used to accompany or accentuate speech. When reviewing our collected data, we realised that almost every story the participants had shared with us included the exchange of certain words or phrases. In some cases, it was actually easier for them to remember what was said as opposed to recalling the exact context in which events took place (location, time of day, etc.).

Another interesting observation discussed on many occasions was how seemingly harmless gestures could be interpreted as offensive when combined with the right words; an obvious example of this would be a thumbs up accompanied by a verbal insult. Of course the opposite can also be achieved; a clearly offensive gesture followed by a gratifying comment can be considered quite friendly in the right circumstances. As we continued to converse, the interdependent relation of spoken language and gestures became more and more indisputable, inspiring us to make this fact evident in our creative work.

The next step was to figure out a way of visually representing how offensive gestures and speech work together within social interactions. Thinking back to the conceptualisation of our MDF laser-cut frames, we immediately saw an opportunity to develop the format further. Based on the idea of separate layers creating a narrative when combined, they were made to demonstrate the importance of context in relation to how and why certain gestures could be considered offensive. Having concluded that language was also an equally essential component, we decided to produce third layer in which words would be represented in the same way as hand-movements and environmental elements. This felt like a natural progression for our laser-cut works, and reinforced its basic concept.

Phrases

As we had used our sketches as a source-material for depicting context and gestures, we opted to follow a similar process for our language layer by selecting key-words and phrases in our recorded conversations. After scripting each conversation, we dissected them, separating definable elements into categories (stories; general observations; opinions; etc.) in order to pinpoint verbal responses that everyone could relate to when thinking about the subject matter. Bearing in mind that our project aims to examines both the act of being offensive as well as being offended, we made sure that the selected quotes illustrated both perspectives. We also paid particular attention in choosing short, poignant phrases.

Once several appropriate quotes were picked out, we discussed ideas for fonts; although our initial thought was to use either a single or two distinctive typefaces in order to guarantee readability, we quickly deduced that the end result would seem to strict, and wouldn’t gel naturally with the hand-drawn attributes of our other laser-cut compositions. We decided to write them out by hand instead, giving them each more a personal trait in accordance to the nature of the quote. This, in turn, allowed us to see whether or not those unique characteristics could be suitably translated on Illustrator.

Gestures

Looking back at the drawings of the three areas, and the gestures described to us in the discussions, Emma created a series of illustrator files that create our third ‘layer’ subject. As the gestures, are quick movements we thought it would be representative to use engraving and almost create a shadow of layers of the hand; as if taking frames from a film. These frames would be engraved, with the priority shape of the hand cut out to emphasise the pinnacle of the movement.

Ideally we would like these layers to be cut from frosted acrylic, as it would create

another completely different colouring, without a defining colour. To add a colour

would be to give the pages a predetermined meaning. Whereas the frosted acrylic

would still be able to let light through and allow all layers to be seen.

Unfortunately after looking into costings of ordering in frosted acrylic we came to realise this wasn’t going to be an option. However I came up with the idea to test some sandpaper on clear acrylic and the outcome worked really well. We got the same effect of clear acrylic however we had full control of the opaqueness, and could alter the shape of the sanding therefore the movement was clearer. There is also a different feeling to the touch with the sanded side; it is another completely different material now.

Rule of 3

We have three main elements , gesture and context split into physical environment and phrases of quotes. Using three varying materials, we hope to echo the elements within the laser cuts. The MDF will represent the strong, stable attributes of each place. The clear acrylic will depict the ephemeral quotes. And a ‘frosted’ acrylic will show the movement within gestures.

Looking into the ‘rule of three’ it seems to be visible in so many differing types of design. Often ‘information presented in groups of three sticks in our heads better than other clusters of items’ . So if we want to optimise our work, and make it as memorable as possible we should utilise the rule. This may also alter how the public view the work. It is human nature to look for patterns within layouts, and three is the smallest pattern you can have. If we can compose our degree show in three, all the outcomes will compliment each other and present a well rounded exhibition.

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |

Degree show setup

Our laser-cut outcomes illustrate the importance of environment and language as context, in relation to how we interpret offensive gestures.

Inspired by our observational drawings and the interviews conducted with our peers, we have three elements to explore the subject; gestures, environment and language.

When combined they create momentary interactions in which context and offensive gestures are brought together to communicate.

We have designed the materials and shapes to reflect the context they represent. The MDF represents the elements of stability found in the environment. The clear acrylic echoes the intangibility of phrases. And the frosted acrylic depicts the movement of gestures.